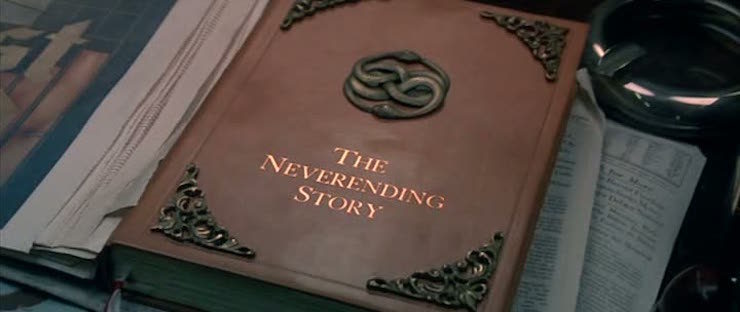

The NeverEnding Story was a classic children’s fantasy of the 1980s, right up there with The Dark Crystal, Labyrinth, Legend, and The Last Unicorn in creating a latticework of terrifying puppets, questionable animation, and traumatizing storylines. It had an added allure for this small, library-loving nerd: it was about a book that never ended. Most fantasies just give you a perfunctory review of some scrolls or an ancient dusty text before galloping back into an action scene, but The NeverEnding Story is literally about a kid sitting in an attic and reading all day—making it both fantasy and Carverian realism as far as I was concerned.

Looking back at it as an adult (more or less), I was surprised by how well it holds up. True, you have to look past some extremely emphatic acting, and Falkor is slightly creepy now that I’m older—although compared to David Bowie’s tights and Molly Grue’s lamentation for her virginity lost youth, he’s really not that bad. But watching it again gave me a completely different experience, not just an exercise in nostalgia.

Here are 9 reasons you should revisit it, too:

Nostalgia

Yes, partly for the movie itself but also for the feeling of being a kid. And being a kid sucks most of the time. You have very little agency, you’re bound by rules you don’t always understand, you often have to eat things that you hate, and there’s usually at least some amount of homework. If you were anything like me, the best days of your childhood were most likely spent huddled under a blanket, reading something—The Hobbit, Earthsea, Harry Potter, Ender’s Game—that took you somewhere else, somewhere where you were definitely not a kid, or at least you had some compensatory magical ability. The NeverEnding Story takes this memory and cranks the dial all the way up, adding a forgotten math test, a spooky attic, and a vicious thunderstorm to create the best possible environment for escapism.

The effects are fantastic!

I mean, they’re not always good, and they don’t quite stand up to The Dark Crystal or other Henson work of that era, but they have a particular homemade flavor. Morla the Ancient One and the Rock Biter are expressive characters who come to life with only a few moments of screen time, and the council of advisors who summon Atreyu are all unique, rather than succumbing to a discount Mos Eisley Cantina feeling. The NeverEnding Story isn’t lifting imagery or ideas from Star Wars, E.T., Henson, or even something like Excalibur. Fantasia feels like a fully-realized, self-supporting world, and the movie is telling a story that, while drawing on archetypes and classic mythological themes, still gives you something new.

The Auryn

The Auryn is still the coolest piece of fantasy jewelry ever. It doesn’t need to be cast into a volcano, it won’t screw up any time streams, and it doesn’t require a piece of your soul. It simply functions as an elegant symbol of eternal return and interconnectedness, and occasionally mystically guides you to the Childlike Empress. No big deal.

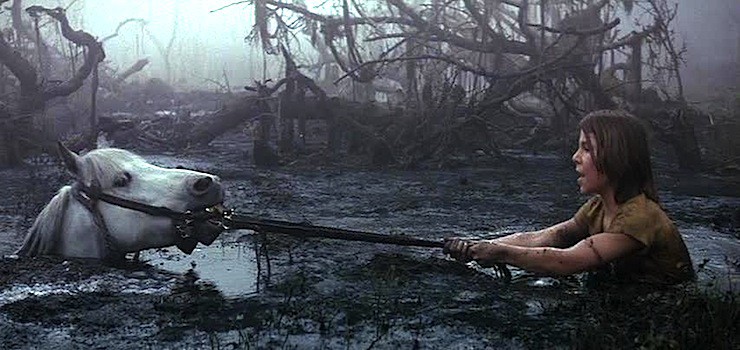

Artax

When you were a kid, Artax’s death was shattering. His death is real, and tragic. Yes, Artax does come back, but only because Bastian—who is just as devastated as the audience—wishes it. I don’t know about the rest of you, but I spent waaay too much time wondering if the Artax at the end was really the same Artax, if the newly-wished-into-existence horse would have the same memories as the original. And does he remember his death? (Like I said, maybe too much time spent on this…)

Watching The NeverEnding Story again as an adult is beneficial in a very specific way: You watch the horse die, it still hurts, and you remember that you’re not the hollowed-out shell of grown-up responsibility you sometimes fear you have become.

See? Helpful.

The Magic Mirror Gate is far more resonant now

To put it a better way, it probably didn’t make any sense at all when you were a kid, but now it will. As a kid, Engywook’s words of caution—“kind people find out that they are cruel. Brave men discover that they are really cowards! Confronted by their true selves, most men run away screaming!”—didn’t sound terribly scary, because they refer to a very adult type of self-doubt. Bastian and Atreyu are both confused by the Mirror—like the kids watching the film, they can’t understand why seeing your true self is so frightening. But what adult would be willing to look into it, and see that their self-image is false?

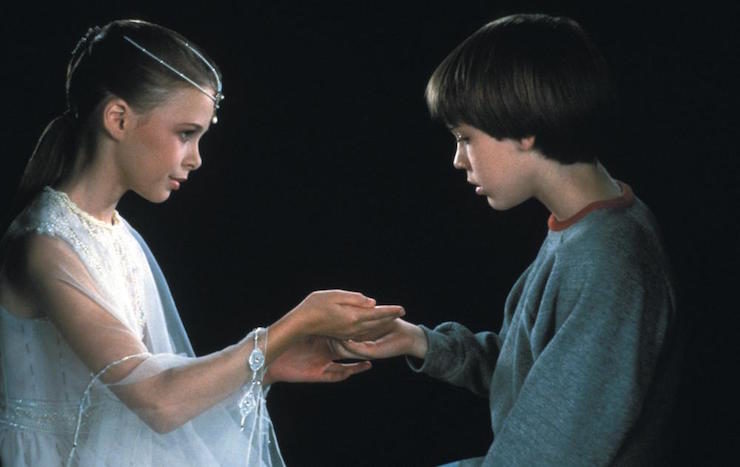

META-PALOOZA. META-GANZA. META-POCALYPSE!

Now we throw the term “meta” around as carelessly as “hipster,” but The NeverEnding Story uses its nested story structure to illustrate a larger point. Atreyu is living his adventure as the hero, but he’s given hints that his life isn’t what he thinks it is. He sees Bastian in the Mirror Gate, hears Bastian scream when Morla first appears, sees his own story depicted in a series of narrative murals, and eventually is directly told by the Empress that Bastian has shared his adventure. Despite this, he never questions his quest. He carries on being a hero, even to the point of challenging Gmork to an unnecessary fight (more on that later) and dies in the Tower without ever realizing that he’s a fictional creation. He has a job to do, and anything beyond that job is irrelevant.

Bastian, meanwhile, also receives clues that he is more involved in the life of Fantasia than he realizes. He hears the Empress tell Atreyu that “others” are sharing Bastian’s adventures: “They were with him in the bookstore, they were with him when he took the book.” Bastian replies with a Hamill-worthy “But that’s impossible!!!” and carries on in his role of nerdy boy reading in an attic. He only truly flips his shit when the Empress addresses him directly to demand a new name. (More on that name in a second.) The movie deftly skips over that bit, and never returns to it, but think about it: those “others” are us, right? As in, the kids sitting on the floor in front of the TV watching the movie? If we’re watching Bastian, and he’s watching Atreyu, then who the hell is watching us?

Now, before we spin off into dorm room musings, I wanted to pull back and say that I don’t think the film was trying to convince us that we’re all in some reality TV show without our knowledge. But I do think they were trying to sneak in a comment about the way we construct our lives. How do we see ourselves? How do we choose our actions? If our lives were books or movies or six-issue mini-trades, what would we want them to look like? I would submit that you could do worse than this:

“If we’re about to die anyway, I’d rather die fighting”

On the one hand the fight with Gmork is Atreyu acting like a heroic automaton. But then there’s that other hand, and that other hand has an amazing moment in it. Think about it—it would be so much easier for Atreyu to give up. The Nothing is coming anyway, right? Gmork doesn’t recognize him, he’s done everything in his power to reach the Human Child—at this point no one could blame him for sitting back with the Rock Biter and waiting for the Nothing to take him.

Instead, he risks a painful death-by-combat with a giant wolf. That’s a hell of a way to rage against the dying of the light.

Bastian recreates the world from a grain of sand

Blakean imagery aside, there’s a great lesson here—a lesson that’s far better for adults than kids. When you’re a kid it’s pretty easy to bounce back from failure and disappointment, because—unless you’re a Peanuts character—you just assume that the next time will go better, and you try again. But once you’re older, and you have a longer list of break-ups, dropped classes, books you haven’t finished reading, books you haven’t finished writing, plus maybe a layoff or two, it gets harder and harder to work up enthusiasm for new projects. Here we have a story where the world really ends, and all the characters we love die—Atreyu and Bastian have both failed. How often do you see a kid fail in a children’s movie? But that failure doesn’t mean that Bastian gets to fall apart and hide in the attic forever—he has to go back to work, and, ironically enough, do exactly what his father told him to do at the film’s beginning. Fantasia is his responsibility now, and he has to rebuild it and take care of it.

Follow Your Urge to Research!

As an adult watching this you can hear the name Moon Child and think, “what the hell? Did Bastian’s grandparents conceive during a Dead show?” Alternatively, you can look up the name Moon Child, and go off on a fabulous Wiki-wormhole leading to Aleister Crowley and the history of 20th Century Magick, which is just fun. But even better, you could dive into the work of The NeverEnding Story’s author, Michael Ende. Ende was one of most beloved children’s authors in Germany, and while not all of his books have been translated, it’s worth the effort to find them. The NeverEnding Story in particular is a fascinating deconstruction of fairy tales, much darker than the film, and one of the most rewarding books I’ve ever read.

Originally published in August 2013.

Leah Schnelbach has never quite managed to keep their feet on the ground, no matter how hard they try. Come scream MOONCHILD at them on Twitter!